What do we know about the links between girls’ education and climate and environment change?

By Camilla Pankhurst

Representatives from around the world recently met in Glasgow for COP26 with 2021 heralded the ‘make or break’ year to avert irreversible impacts upon our planet.

But for billions of people, climate change is not a future problem but a lived reality. Climate and environment issues are already wreaking havoc through extreme weather events, depleting resources, and deteriorating livelihoods. It is the poorest households in the poorest regions hardest hit, with women and girls disproportionately affected due to existing gender inequalities.

As experts grapple with these challenges, the question of the relationship of climate change with girls’ education has been building momentum. On the one hand advocates point to the devastating impact of climate change and environmental degradation on education, and on the other the potential for education, particularly of girls, to accelerate both mitigation of and adaptation to climate change. And while education hasn’t previously featured prominently at COP, there are signs this is shifting and that world leaders are waking up to the links.

But what do we really know about these links between girls’ education and climate change in lower income countries?

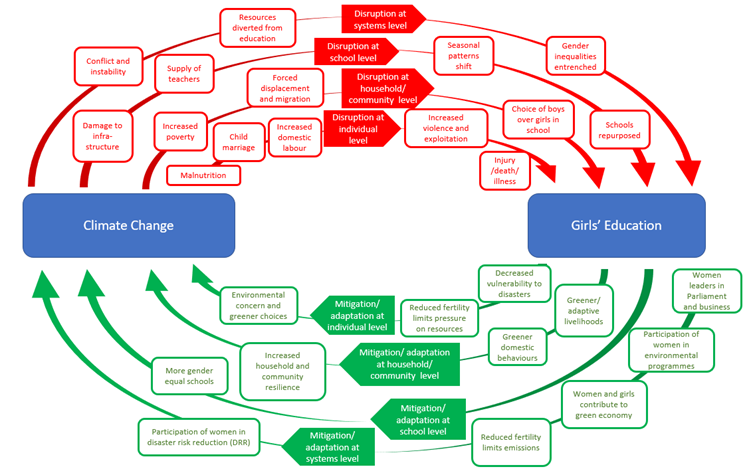

To help answer, as part of my MA degree in Education and International Development at UCL Institute of Education, I conducted a rigorous review of the evidence base, which included 86 studies published from January 2012 to March 2021. The full report, including a detailed methodology, will be available soon. Based on the literature, I developed a conceptual framework which depicts layered relationships. The top half outlines wide-ranging, often long-lasting, and overwhelmingly negative effects of climate change – both direct effects from severe weather events, and slower onset environmental changes – on girls’ education (the red arrows). The bottom half shows potential positive impacts of girls’ education on climate change (the green arrows).

So, what did the review find?

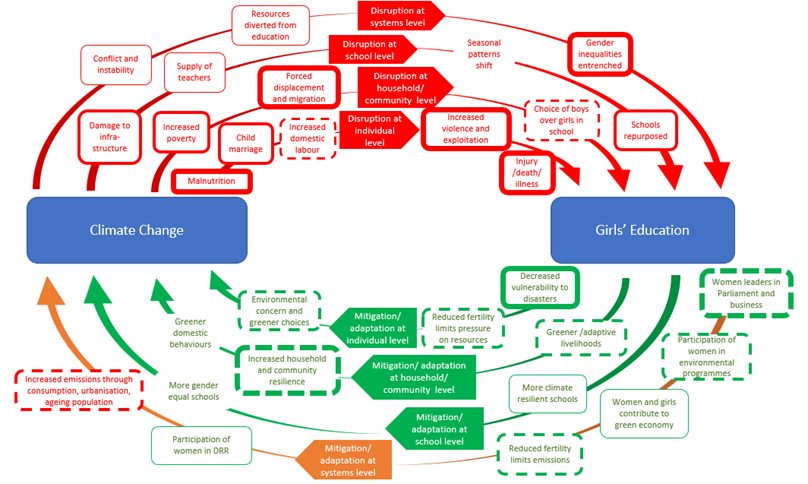

The review evaluated quality, thus identifying areas of relative strength and weakness in the evidence base. Of the 86 studies included after screening, 52 were assessed to be of high- or moderate-quality, primary or secondary evidence. The remaining studies were theoretical or low quality and judged not to provide reliable evidence for the research question. The diagram below is a visual depiction of the volume and consistency of these 52 studies against the conceptual framework.

What does this show?

The review found that there is evidence from lower income countries of the pathways between girls’ education and climate change, but this is nascent and mixed.

It found the strongest evidence for the negative impacts of climate change on girls’ education, particularly at the individual and household/community level. That climate change drives harmful processes associated with girls’ education such as malnutrition; child marriage; injury, illness and death; violence and exploitation; increased poverty; and forced displacement is hardly surprising, but nonetheless deeply concerning. At the school level, there was clear evidence that climate change causes damage to infrastructure, which can mean children are out of school for months after disasters strike.

The evidence for the impacts of girls’ education on climate change were more uncertain. The review found strong evidence that girls’ education reduces individual vulnerability to disasters and suggested it improved household and community resilience. There is also evidence to suggest that women’s leadership in Parliament has a positive impact. But very little evidence showed that women’s participation in the ‘green economy’, environmental programmes or Disaster Risk Reduction have benefitted the climate change agenda. This is not to say that those links do not exist – the review just did not find strong evidence for them. Further high quality research is needed to examine these pathways between girls’ education and climate change, particularly to identify causal relationships and dependencies.

Some surprises

The evidence on climate change’s impact on domestic labour and choice of boys over girls in school is more nuanced than the dominant narrative (which assumes girls are always disadvantaged) suggests. In some contexts, boys are actually more likely to be taken out of school to do domestic labour – such as renovating damaged buildings – than girls. There were mixed findings on education’s role in encouraging greener choices, with some studies suggesting that expansion of ‘Western’ education could have a negative impact on climate change.

The review showed that education is one factor amongst many in women and girls’ relationship with climate change. Mixed findings for the bottom half of the conceptual framework were often due to other gender inequality factors that prevented women from participating meaningfully in community discussions or environmental programmes. This suggests that girls’ education alone will not be a ‘silver bullet’ to solve climate change and requires us to take diversity and intersectionality into account in our efforts.

The link between girls’ education and mitigation of climate change is a hotly contested topic. While some argue that there is a link between girls’ education, slower population growth and reduced emissions, others point to major ethical concerns of richer countries seeking to control population levels in poorer countries to slow global warming.

This review suggests that the relationship is not clear for two major reasons. First, the assumed causal link between education and reduced fertility is perhaps not as strong as thought. Second, the low relative and absolute emissions of fast-growing populations, particularly in Africa, means that slowing population growth is unlikely to be an effective use of scarce political capital. Coupled with evidence of harmful effects from efforts to slow population growth for environmental protection, this review suggests that educating girls for the instrumental sake of reducing fertility is not the path to take.

That is not to say that we should not advance girls’ reproductive rights and empower them to choose their family size. This is critical and speaks to education’s wider positive (and intergenerational) impact on gender equality through increased choice, reduced child marriage, reduced maternal mortality and improved child health and educational outcomes.

So, what should we do?

There are some clear implications of the review, which should be addressed in the follow up to COP26:

1. Act with urgency to protect girls from negative impacts of climate change. Efforts to adapt must be prioritised, with education systems made more resilient. This includes ‘climate proofing’ schools, securing equitable provision of distance learning and scaling up emergency education to respond to extreme weather events and displacements.

2. Focus on the quality of education and ensure girls gain the foundational skills of literacy, numeracy and core socio-emotional skills they need to realise the positive potential of education to affect climate change. Currently over 90 percent of primary-age children in low-income countries cannot read or do basic maths by the end of primary school. Without these skills, none of the positive potential pathways in the conceptual framework will become reality.

3. Ramp up research to start filling some of the gaps in the pathways on the conceptual framework and answer important questions about what works to adapt to and mitigate climate change, particularly in terms of systemic education reform. Further context-specific evidence is urgently needed to better understand how the relationship between girls’ education and climate change is localised in different situations and for different groups to avoid policies and practice which assume universal experiences of climate change for all girls and women. Determining the intrinsic qualities of education that are most likely to lead to positive instrumental outcomes should be a priority.

Camilla Pankhurst is employed as an education advisor for the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Opinions and ideas expressed here are her own, not her employer’s.